DEVELOPMENTALLY DISABLED CLIENTS DIED, WHEN THE GOVERNOR, AND DDS ALLOWED THE SAME THINGS THEY ARE I

- Jun 23, 2018

- 11 min read

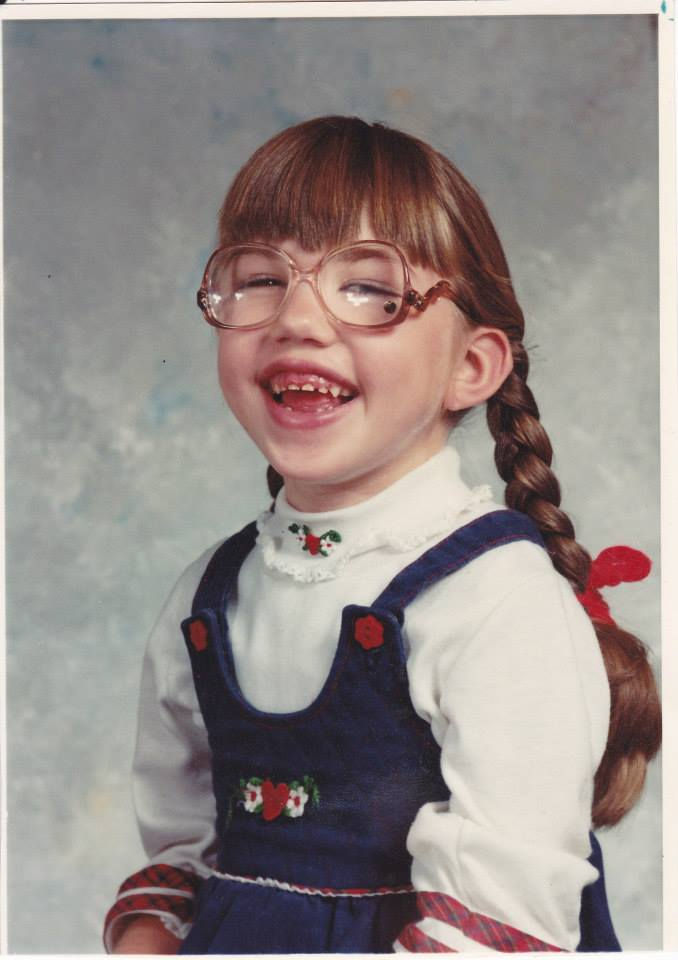

JUST LOOK AT THAT SMILE! YES, SHE IS MUCH YOUNGER HERE, BUT THE SMILE CONTINUES. WILL SHE DIE SMILING - NON KNOWING, THAT THE STATE OF CT IS FAILING TO KEEP HER SAFE, WHILE ALLOWING HER GROUP HOME OPERATOR TO INVESTIGATE CLAIMS OF MEDICAL NEGLECT CAUSING INJURY TO ROBIN LYNN? READ THIS ARTICLE FROM 2013, PROBLEMS JUST LIKE HERS ARE NOTED - OPERATOR SELF INVESTIGATION, AND IN AT LEAST ONE CASE - MEDICATIONS ADDED CAUSING FALLS! IS THIS WHY WHEN YOU CALL THE GOVERNOR'S OFFICE HIS STAFF PRETENDS THEY DON'T KNOW A THING ABOUT ROBIN LYNN? THE DDS COMMISSIONER REMAINS SILENT???? THE GUARDIAN IS PROPERTIED TO BE UNWILLING TO FACE THE TRUTH? PLEASE HELP ME FIGHT TO NOT ONLY SAVE ROBIN FROM FURTHER INJURY, BUT THE POSSIBILITY OF DEATH.!

HERE IS THE ARTICLE FROM 2013

JOSH KOVNER, MATTHEW KAUFFMAN and DAVE ALTIMARIThe Hartford Courant

Paula Berardi thought she'd found a safe haven for her developmentally disabled daughter, Tracey Hilliard.

Four other group homes hadn't worked out, and Tracey, who also had medical problems, was a handful at home. The state Department of Mental Retardation put Tracey with a licensed provider named Sophie Caro, who cared for several developmentally disabled adults at her home in Meriden.

The placement proved tragic. Tracey Hilliard, 30, drowned in a pond at a campground in Clinton on Aug. 4, 2004. Though Hilliard couldn't swim and her treatment plan said she must have a life preserver, Caro let her go in the water with an inner-tube, a state investigation concluded. There was no lifeguard and Caro couldn't swim either, according to the investigation.

Investigators attributed Hilliard's death to neglect on Caro's part, and her license was pulled.

A Courant investigation has discovered that Hilliard is among dozens of developmentally disabled people who died in public and private group homes, institutions and nursing homes from 2004 through 2010 in cases where investigators cited abuse, neglect or medical error as a factor.

Those conditions were cited during investigations into the deaths of 76 intellectually disabled people receiving state services — or 1 out of every 17 clients who died over those seven years, a Courant investigation has revealed.

Another 28 deaths involved allegations of abuse or neglect that couldn't be substantiated by state investigators. Two deaths are still under investigation.

The Courant's review of state records associated with the more than 100 deaths revealed systemic flaws in the care of the developmentally disabled, ranging from breakdowns in nursing care to gaps in the training of staff to lapses in agency oversight.

Developmentally disabled people were scalded to death in bathtubs; were fatally injured in falls while on medication that affected their balance; choked to death on solid food while on ground-food diets; died of illnesses despite showing symptoms for days or even months; and succumbed while being physically restrained.

For the families of the victims, a sense of betrayal compounds their grief.

"I was devastated — and mad," said Berardi, of Clinton. "Tracey died senselessly. If they followed the rules, my daughter would still be alive today. She was a human being. She deserved the same rights as anyone else."

James McGaughey, executive director of the Office of Protection and Advocacy for Persons With Disabilities, said one theme runs through the reports of abuse and neglect: Many of the deaths could have been prevented.

For example, Rebecca Wojcik, 59, stepped out of the bathtub at her group home in March 2004 with burns over nearly half her body. Two group-home workers failed to test the water before she got in. With her skin peeling off her body, Wojcik was taken to a hospital burn unit, where she died, records show.

In another case, Brian Francis Casey, 53, had been suffering from pneumonia for months, an investigation concluded. With his vital signs deteriorating, the staff of the state home sent him to the emergency room. He was dead two days later, his weight down to 55 pounds.

In 2001, a Courant investigation of deaths of intellectually disabled people in state care identified 36 cases from 1990 to 2000 in which abuse or neglect played a role in the death. The Courant found more than twice as many cases from 2004 to 2011, despite added oversight by the agency now known as the Department of Developmental Services. Now, budget pressures are further straining a system that many believe has reached its breaking point.

Danger Always Lurking

The deaths in 2004-2010 ranged from a 21-year-old killed in a car crash to an 86-year-old who died after staff at a nursing home failed to heed a doctor's order to seek emergency medical care, according to case summaries prepared at The Courant's request by OPA.

The state does not disclose the names, but The Courant, through an examination of public records and interviews with families, was able to identify most of the individuals who died.

Deaths came in large, state-run facilities on expansive campuses and in small group homes on residential streets. Some who died led mostly independent lives; others were severely disabled with the mental capacity of a young child.

In addition to the chokings, fatal falls, scaldings and drownings, the deaths included clients who got sick, exhibited signs and symptoms of illness, and died without receiving proper or timely medical treatment. In several cases, staffing and training issues led to breakdowns in care.

Kallif Mysogland, 30, who had behavior problems, died after he was restrained three separate times in one night by three staff members at a state residential facility in Meriden in 2006. His medical records said certain protective holds could lead to stroke or heart attack. During the third restraint, Mysogland began to bleed from his face, went limp and died of cardiac arrest.

There have also been more than 6,000 reports of non-fatal abuse and neglect over the past decade involving individuals with intellectual disabilities, including hundreds of cases of sexual abuse, state records show. And more than 40 percent of cases reported at privately run residential programs were investigated by the programs themselves, although state officials say the investigations were monitored by government agencies.

David Kassel, who acquired the abuse and neglect data and works with the Southbury Training School Home and School Association, said there is a conflict in allowing agency employees to investigate their employers.

"Relying on group home provider organizations to investigate allegations of abuse and neglect in their own programs is putting the fox in charge of the henhouse," Kassel said.

Among issues raised by patient advocates is the reliance on "on-call" nurses, who are responsible for several group homes at once. These nurses often dispense medical instructions over the phone rather than in person, occasionally resulting in a misdiagnosis, with fatal consequences, records indicate.

In February 2006, the staff at a group home phoned the on-call nurse to report that 46-year-old Kathy Seleman was ill. The nurse didn't answer or call back. Three and a half hours later, the staff called again and said Seleman had a fever and vomited. This time, the nurse said to call her back if the symptoms worsened. By the following morning, the staff had called back. The nurse prescribed Tylenol, but never visited Seleman. Two days would pass. At 3:30 a.m. on the third day, "staff checked and found her to be blue and called 911, then began initiating CPR," according to the investigation report. Seleman was dead on arrival at the hospital.

Investigators with the protection and advocacy office found neglect on the part of the on-call nurse and three of the group-home staff members. The investigators said that the nurse failed to uphold proper standards of care, and that the staff never accurately communicated Seleman's changing symptoms to the nurse.

The office of protection and advocacy did what it often does in these cases: recommended that the state-monitored group home adopt standards that are already called for in state regulations or guidelines. In this case, OPA said the group home should ensure that staff members are trained in recognizing symptoms, and should develop a procedure for on-call nurses that specifies "when and how" a client is to be "physically assessed." Without the authority to impose sanctions, the OPA recommended to the private group home that "disciplinary action should be considered for those employees who were determined neglectful in their job."

James McGaughey, executive director of the OPA, said group homes increasingly rely on on-call nurses who make diagnoses over the phone without seeing the clients. The result, he said, is that fewer medically trained workers are involved in patient care.

"There is a lack of clarity as to the role of nurses who are on call and what they are supposed to be doing," McGaughey said. "What happens is that group home managers are making medical decisions even though they don't have the medical background to do so."

Also, in some cases, staff members either weren't trained to handle certain medical emergencies or were reluctant to use their training.

Dory McGrath, director of nursing for the state Department of Developmental Services, said "there may have been issues in the past where [an on-call nurse] didn't respond fast enough; it has happened."

But she did not agree that there is a "lack of clarity" about the role of on-call nurses.

The expectation, she said, is that staff members at the group home give the on-call nurse accurate information, and the nurse makes a decision about treatment.

"If there is any question, the person would be sent to the emergency room," McGrath said.

How We Got Here

The Department of Developmental Services serves nearly 16,000 adults at any given time. The cost is $124,000 to $325,000 a year to care for one person with intellectual disabilities and medical needs, depending on the size of the facility, the level of medical need and the scope of services. Even with a budget topping $1 billion, the department and the providers have been unable to consistently maintain ideal staffing levels, training programs and oversight, say advocates and state officials. Connecticut has a network of 870 group homes and a host of other licensed facilities.

Group-home companies and client advocates say state funding hasn't kept pace with the cost of care. Last fall, DDS trimmed more than $10 million from the pot of money available to the group-home contractors as part of a series of cuts by Gov. Dannel P. Malloy. The reduction at DDS followed four years of no contract increases for the private providers, said Ron Cretaro, executive director of the Connecticut Association of Nonprofits.

The money strain has consequences, say client advocates.

"You're creating this system where you're asking people to do more with less, and it's going to take its toll," said Leslie Simoes, executive director of The Arc Connecticut, the state's largest advocacy group for people with developmental disabilities.

Absent major reforms, "we are going to see increasing neglect, increasing unsafe situations," Simoes said.

Thirty-five years ago, the group-home model was considered a panacea.

The Mansfield Training School, a sprawling institution, had been targeted in a 1978 federal class-action lawsuit charging that conditions there violated the civil rights of residents. The agency then known as the Department of Mental Retardation began in earnest to line up private group homes of four to six people in neighborhoods throughout the state for former Mansfield residents, and, later, for people who otherwise would have gone to the Southbury Training School. The Southbury facility remains open, with more than 400 residents, but stopped accepting new admissions in 1986.The state wants to relocate the remaining residents and close the facility for good, but many of the residents' families want to keep the campus open.

At first, training for the privately owned group home workers was virtually non-existent.

"I was literally hired off the street with no training and no experience,'' Simoes said of her first minimum-wage job working directly with profoundly disabled people in a group-home.

Over the last 15 years, training has improved. Group-home workers are required to be certified in CPR and first aid, for example.

But the average pay for direct-care workers in private group homes — about $15.50 an hour — is still not high enough to attract and hold the most experienced and skilled workers and reduce the industry's high turn-over rate. Starting pay is about $12 an hour, Cretaro said.

"It's a revolving door,'' Simoes said. "You want to know what the talk is out there? The talk among the professionals in this field is about the lack of training, and how providers can't maintain high-quality staff with what they're paying them.''

She and other advocates are pressing for a system that would funnel state funding, support services and other resources to those families who want to care for their intellectually disabled sons and daughters at home. The remaining group homes would specialize in serving clients with complex medical or behavioral needs and those with no other options.

DDS Commissioner Terrence W. Macy supports this shift and has made it part of his five-year plan.

Meanwhile, group homes and several larger state-run campuses will remain the primary residence for more than 4,500 people with intellectual disabilities.

Beyond the staffing, pay and training issues are factors that complicate the already challenging abuse and neglect investigations.

For example, autopsies are not routinely performed in deaths of developmentally disabled people who were in state care, even when substandard treatment is suspected. And on 26 occasions between 2008 and 2011, nursing homes failed to notify DDS that an intellectually disabled patient had died. In some cases the notification, required by state and federal law, wasn't made until several months after a person's death.

Seeking Solutions

Some of the victims of confirmed abuse, neglect or medical error died in group homes and other facilities that were run directly by DDS or by private DDS contractors. Some had been transferred to a nursing home or a hospital. Still others lived in community training homes, which have fewer clients than a group home. Some had lived at the Southbury Training School, or on DDS regional campuses. A handful of the victims were living at home. All were receiving at least minimal services from DDS.

Macy, the commissioner, said his department is taking specific steps to reduce the potential for fatal mistakes. For example, to address choking deaths, Macy said DDS nursing administrators are working with the state Department of Public Health to instill "better meal planning and food delivery" practices in nursing homes.

"We're concerned any time we have an untimely death anywhere," said Macy, who was appointed by Gov. Dannel P. Malloy in April 2011.

But Macy, who ran group homes for 20 years, said the ultimate reform is to have fewer DDS clients in group homes and nursing homes.

"We're trying earnestly to reduce the number of our people living in nursing homes," he said. "It's just not the best model of support."

And Macy said those who run and regulate the system of care have tended "to put all our eggs in the group-home basket. Some people just don't need that level of care."

Simoes, from the Arc Connecticut, agreed. She said that, a generation ago, group homes were seen as a progressive alternative to institutionalization. But "the group home model was based on the institutional model, often with regimented schedules that limit clients' ability to make decisions for themselves."

Macy said he wants to gradually get intellectually disabled people out of these settings and back with their families, with state services provided directly to parents, guardians or caregivers.

"In four or five years, we want to see a flip in the numbers of people who are in group homes, and in family homes — because that is a far more appropriate setting."

Asked if that would improve the health and safety of DDS clients, Macy said, "I would think so."

"The key is getting families involved," he said. "That's a far more responsive system. There's no stronger dynamic in the world than a mother" concerned about her son or daughter.

'Conscious Disregard'

Paula Berardi's daughter, Tracey Hilliard, had a profound intellectual disability.

"Tracey was on about the 2-year-old level. She had scoliosis and had two Harrington rods put in her back at about 8 years old," said Berardi. "She had Marfan's syndrome and she had optic atrophy. She saw upside down."

Marfan's syndrome is a genetic disorder of the body's connective tissue. People with the disease are often unusually tall; Tracey was over 6 feet.

In early August 2004, Caro took Tracey and several other adults in her care to a campground in Clinton for a sleep-over, picnicking and swimming.

There was no lifeguard at the campground.

DDS water-safety regulations issued in June 2003, more than a the year before Hilliard's death, say a "certified lifeguard must be on duty at the location, or included with the group, to swim at any ocean, lake or pond. If there is no lifeguard, none of the individuals shall swim."

Tracey Hilliard's body was found in about six feet of water, said her sister, Tena Larch.

In substantiating allegations of abuse and neglect against Caro, OPA investigators said Caro "indicated that she, herself, was unable to swim or put her head under water and moreover, stated that she knew no lifeguard was on duty that particular day."

The OPA investigators said Caro's actions "evidenced a conscious disregard for the necessary supervision" of Tracey Hilliard.

Larch wondered, "Why isn't every caretaker certified in water safety and CPR?"

The family settled a wrongful-death lawsuit with the state in 2007. As is the case in many of these actions, the state took a large portion of the settlement as payment for Tracey's care, Larch said. Caro could not be reached for comment. Public records indicate she moved from the Millbrook Road home in Meriden to Florida. She did not respond to a letter mailed to the Deltona, Fla., address from the Courant.

"We still don't have all the answers," Larch said. "It's still an open case in our minds. It's not closed in any way, shape or form, even though Tracey's gone."

E-mail Josh Kovner, jkovner@courant.com, Matthew Kauffman, mkauffman@courant.com and Dave Altimari, daltimari@courant.com

Comments